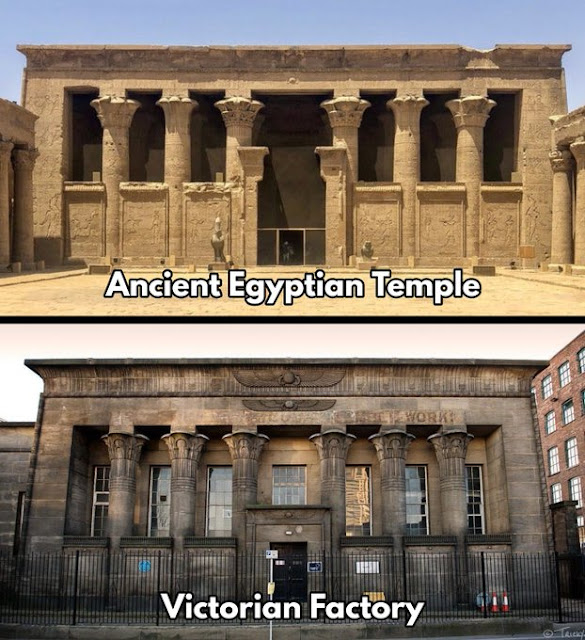

This building is not a palace, court, library, or theatre — it's a 19th century factory in northern England.

And its design was directly based on the Ancient Egyptian Temple of Horus in Edfu.

Why are Victorian factories more interesting than the most expensive modern buildings?

So, this is the main entrance and counting house of a factory built near the English city of Leeds in the 1830s by the architect Joseph Bonomi, with help from the Scottish painter and Egyptologist David Roberts. They built it for the industrialist and mill owner John Marshall. Its style, unsurprisingly, is known as Egyptian Revival.

Indeed, it is an almost direct recreation of the Temple of Horus in Edfu, which was built in the 3rd century BC under the Ptolemaic dynasty. Roberts had been there and sketched the temple himself; the façade was based on his drawings. Hence its name: Temple Works Flax Mill.

Directly adjacent to the main entrance and offices is the factory itself, which was once crowned with a chimney in the shape of an obelisk and was apparently inspired by another famous Ancient Egyptian temple complex at Dendera.

But this was no mere vanity project. The Temple Works Flax Mill was, upon completion in 1840, the largest single-floor factory in the world. Nearly 3,000 people were employed here and it was equipped with the most advanced technology available.

One of its brilliant design features is the array of more than sixty conical skylights in its extensive roof. What might have been a rather dingy space — given its size, which is over two acres — was instead illuminated at all times by natural light.

The factory was also installed with a complex system of ducts, vents, and pumps to manage its internal temperature, baths for all workers, and a custom-built 240 horsepower steam engine. In 1840 this factory was high-tech, cutting edge industry.

Flax mills must stay humid, otherwise linen thread dries out and becomes unusable. How did Marshall and Bonomi deal with this? Atop the forest of cast iron pillars supporting the mill's huge ceiling are a series of brick vaults covered in rough plaster. Over these was laid an impermeable layer of coal-tar and lime, upon which was then placed a bed of soil planted with grass; all of this so no moisture could possibly escape.

To keep the grass roof tidy flocks of sheep were regularly grazed on it. A clever and sustainable form of climate control, decades before air-conditioning was invented.

The Temple Works Flax Mill was a technical triumph, primed for a production line of maximum efficiency. And yet, amid a highly commercial environment, ostensibly driven by nothing other than profit, John Marshall wanted to build a factory which was *more* than just a highly productive industrial facility.

He believed the aesthetics of a working environment were also important, and wanted to give his employees a place of work that was not only functional but beautiful and inspiring too.

So we shouldn't view this façade of monumental papyriform columns, friezes, and cornices as a historical oddity. It speaks to a fundamental view of architecture as something more than merely "useful". Temple Works is a monument of aesthetics *and* functionality — and proof that they can be combined.

Marshall's Egyptian Revival project extended well beyond the architecture of the building; the steam-powered machinery custom built for its interior was also decorated with Egyptian motifs, including winged solar disks and scarabs. This was a total project in which every detail was considered: architecture, engineering, technology, aesthetics, and working conditions fully united under one extraordinary roof.

But Temple Works is no longer a flax mill. It was decommissioned in the late 19th century when competition from abroad rendered it unprofitable, to be replaced first by a box factory and then, in the 20th century, by a mail order firm.

Most recently the Temple Works has lain dormant for over two decades, falling into a state of disrepair and threatened by collapse. But, thankfully, this situation is now set to be reversed.

The British Library intend to take over and repair Temple Works, with the ultimate goal of storing books there and creating a new public space in the area — all while preserving important local heritage. Surely a happy ending for a truly remarkable bit of 19th century industrial architecture.

But there is also a moral to the story. After all, if John Marshall only built a "functional" factory, then there wouldn't have been a campaign to save Temple Works and it would never have become such an iconic place.

But Marshall was building for all time, looking to the future rather than the present day alone. His desire was to create a place both of lasting usefulness and enduring beauty. When we do this — when we consider our descendants and not only ourselves — this is the sort of architecture we get.

Not every building should look like an Ancient Egyptian temple, of course, but as far as factories go... there's a lot we could learn from Temple Works Flax Mill.

%20and%20his%20crown%20prince%20Sennacherib.jpg)

Комментариев нет:

Отправить комментарий